Project Gemini

| McDonnell Gemini spacecraft | ||

|---|---|---|

Gemini 7 in orbit, as seen by the crew of Gemini 6. |

||

| Volume: | 90 ft³ | 2.55 m³ |

| Weights | ||

| Retrograde module: | 1,303 lb | 591 kilograms (1,300 lb) |

| Equipment module: | 2,815 lb | 1,277 kilograms (2,820 lb) |

| Total: | 8,490 lb | 3,851 kilograms (8,490 lb) |

| Rocket engines | ||

| Retros (solid fuel) x 4: | 2,500 lbf ea | 11.12 kN |

| Reentry Control System (N2O4/MMHH) x 16: | 25 lbf ea | 111 N |

| OAMS (N2O4/MMHH) x 2: |

85 lbf ea | 378 N |

| OAMS (N2O4/MMHH) x 6: |

100 lbf ea | 445 N |

| OAMS (N2O4/MMHH) x 8: |

25 lbf ea | 111 N |

| Performance | ||

| Endurance: | 14 days | 206 orbits |

| Apogee: | 250 miles | 402 kilometres (250 mi) |

| Perigee: | 100 miles | 160 kilometres (99 mi) |

| Spacecraft delta v: | 728 ft/s | 222 m/s |

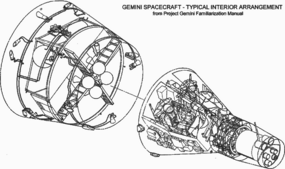

| Gemini spacecraft diagram | ||

Gemini spacecraft diagram (NASA) |

||

| McDonnell Gemini Spacecraft | ||

Project Gemini was the second human spaceflight program of NASA, the civilian space agency of the United States government. Project Gemini was conducted between Projects Mercury and Apollo, with 10 manned flights occurring in 1965 and 1966. Its objective was to develop techniques for advanced space travel, notably those necessary for Apollo, whose objective was to land humans on the Moon. Gemini missions included missions long enough for a trip to the Moon and back, the first American spacewalks, and new orbital maneuvers including rendezvous and docking. All manned Gemini launches used Titan II GLV boosters.[1]

Contents |

Program objectives

After the existing Apollo program was chartered by President John F. Kennedy on May 25, 1961 to land men on the Moon, it became evident to NASA officials that a follow-on to the Mercury program was required to develop certain spaceflight capabilities in support of Apollo. Originally introduced on December 7 as Mercury Mark II, it was re-christened Project Gemini on January 3, 1962. The major objectives were:[2]

- To demonstrate endurance of humans and equipment to spaceflight for extended periods, at least eight days required for a Moon landing, to a maximum of two weeks

- To effect rendezvous and docking with another vehicle, and to maneuver the combined spacecraft using the propulsion system of the target vehicle

- To demonstrate Extra-Vehicular Activity (EVA), or space-"walks" outside the protection of the spacecraft, and to evaluate the astronauts' ability to perform tasks there

- To perfect techniques of atmospheric reentry and landing at a pre-selected location

- To provide the astronauts with zero-gravity and rendezvous and docking experience required for Apollo

Spacecraft

Gemini's primary difference from Mercury was that the earlier spacecraft had all systems other than the reentry rockets situated within the capsule, most of which were accessed through the astronaut's hatchway. In contrast, Gemini housed power, propulsion, and life support systems in a detachable Equipment Module located behind the Reentry Module, which made it similar to the Apollo Command/Service Module design. Many components in the capsule itself were reachable through their own small access doors.

The original intention was for Gemini to land on solid ground instead of at sea, using a Rogallo wing paraglider rather than a parachute, with the crew seated upright controlling the forward motion of the craft. To facilitate this, the paraglider did not attach just to the nose of the craft, but to an additional attachment point for balance near the heat shield. This cord was covered by a strip of metal which ran between the twin hatches. However, this design was ultimately dropped and parachutes were used in a conventional nose-up sea landing.

Early short-duration missions had their electrical power supplied by batteries; later endurance missions used the first fuel cells in manned spacecraft.

The "Gemini" designation comes from the fact that each spacecraft held two crewmen, as "gemini" in Latin means "twins". Gemini is also the name of the third constellation of the Zodiac and its twin stars, Castor and Pollux.

Unlike Mercury, which could only change its orientation in space, the Gemini spacecraft could translate in all six directions, and alter its orbit. It was designed to dock with the Agena Target Vehicle, which had its own large rocket engine which was used to perform large orbital changes.

Gemini was the first American manned spacecraft to include an onboard computer, the Gemini Guidance Computer, to facilitate management and control of mission maneuvers. It was also unlike other NASA craft in that it used ejection seats, in-flight radar and an artificial horizon—devices borrowed from the aviation industry. Using ejection seats to propel astronauts to safety was first employed by the Soviet Union in the Vostok craft manned by cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin.

The Gemini program cost $5.4 billion.

Team

Gemini was designed by a Canadian, Jim Chamberlin, formerly the chief aerodynamicist on the Avro Arrow fighter interceptor program with Avro Canada. Chamberlin joined NASA along with 25 senior Avro engineers after cancellation of the Arrow program, and became head of the U.S. Space Task Group’s engineering division in charge of Gemini. The prime contractor was McDonnell Aircraft, which had also been the prime contractor for the Mercury capsule.

In addition, astronaut Gus Grissom was heavily involved in the development and design of the Gemini spacecraft. He writes in his posthumous 1968 book Gemini! that the realization of Project Mercury's end and the unlikelihood of his having another flight in that program prompted him to focus all of his efforts on the upcoming Gemini Program.

The Gemini program was managed by the Manned Spacecraft Center, Houston, Texas, under direction of the Office of Manned Space Flight, NASA Headquarters, Washington, D.C, Dr. George E. Mueller, Associate Administrator of NASA for Manned Space Flight, served as acting director of the Gemini program. William C. Schneider, Deputy Director of Manned Space Flight for Mission Operations, served as mission director on all Gemini flights beginning with Gemini VI.

Guenther Wendt was a McDonnell engineer who supervised launch preparations for both the Mercury and Gemini programs. His team was responsible for completion of the complex pad close-out procedures just prior to spacecraft launch, and he personally closed the hatches before flight. The astronauts appreciated his taking absolute authority over, and responsibility for, the condition of the spacecraft and developed a good-humored rapport with him.[3]

Astronauts

The following astronauts flew on the 10 manned Gemini missions:

| Group | Astronaut | Service | Mission |

|---|---|---|---|

| Astronaut Group 1 | L. Gordon Cooper | USAF | Gemini V |

| Virgil "Gus" Grissom | Gemini III | ||

| Walter M. Schirra | USN | Gemini VI-A | |

| Astronaut Group 2 | Neil A. Armstrong | Civilian | Gemini VIII |

| Frank Borman | USAF | Gemini VII | |

| Charles "Pete" Conrad | USN | Gemini V | |

| Gemini XI | |||

| James A. Lovell | USN | Gemini VII | |

| Gemini XII | |||

| James A. McDivitt | USAF | Gemini IV | |

| Thomas P. Stafford | Gemini VI-A | ||

| Gemini IX-A | |||

| Edward H. White II | Gemini IV | ||

| John W. Young | USN | Gemini III | |

| Gemini X | |||

| Astronaut Group 3 | Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin | USAF | Gemini XII |

| Eugene A. Cernan | USN | Gemini IX-A | |

| Michael Collins | USAF | Gemini X | |

| Richard F. Gordon | USN | Gemini XI | |

| David R. Scott | USAF | Gemini VIII |

| Mission | Commander | Group | Flight # | Pilot | Group | Flight # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemini III | Grissom | 1 | 2 | Young | 2 | 1 |

| Gemini IV | McDivitt | 2 | 1 | White | 2 | 1 |

| Gemini V | Cooper | 1 | 2 | Conrad | 2 | 1 |

| Gemini VI | Schirra | 1 | 2 | Stafford | 2 | 1 |

| Gemini VII | Borman | 2 | 1 | Lovell | 2 | 1 |

| Gemini VIII | Armstrong | 2 | 1 | Scott | 3 | 1 |

| Gemini IX | Stafford | 2 | 2 | Cernan | 3 | 1 |

| Gemini X | Young | 2 | 2 | Collins | 3 | 1 |

| Gemini XI | Conrad | 2 | 2 | Gordon | 3 | 1 |

| Gemini XII | Lovell | 2 | 2 | Aldrin | 3 | 1 |

Crew selection

Deke Slayton, as head of the Astronaut Office, had the main role in the choice of crews for the Gemini program. With Gemini it became a procedure that each flight had a primary crew and backup crew, and that the backup crew would rotate to primary crew status three flights later. Slayton also intended for first choice of mission commands to be given to the four remaining active astronauts of the Mercury Seven: Alan Shepard, Grissom, Cooper, and Schirra. (John Glenn had retired from NASA in January 1964 and Scott Carpenter, who was blamed by some in NASA management for the problematic reentry of Aurora 7, was on leave to participate in the Navy's SEALAB project and was grounded from flight in July 1964. Slayton himself continued to be grounded due to a heart problem.)

In late 1963, Slayton selected Shepard and Stafford for Gemini 3, McDivitt and White for Gemini 4, and Schirra and Young for Gemini 5 (which was to be the first Agena rendezvous mission). Backup crew for Gemini 3 was Grissom and Borman, who were also slated for Gemini 6, to be the first long-duration mission. Finally Conrad and Lovell were assigned as backup crew for Gemini 4.

Delays in the production of the Agena Target Vehicle caused the first rearrangement of the crew rotation. The Schirra and Young mission was bumped to Gemini 6 and they now were the backup crew for Shepard and Stafford. Grissom and Borman now had their long-duration mission assigned to Gemini 5.

The second rearrangement occurred when Shepard developed Ménière's disease, an inner ear problem. Grissom was then moved to command Gemini 3. Slayton felt that Young was a better personality match with Grissom and switched Stafford and Young. Finally, Slayton tapped Cooper to command the long-duration Gemini 5. Again for reasons of compatibility, he moved Conrad from backup commander of Gemini 4 to pilot of Gemini 5, and Borman to backup command of Gemini 4. Finally he assigned Armstrong and Elliot See to be the backup crew for Gemini 5.

The third rearrangement of crew assignment occurred when Slayton felt that See wasn't up to the physical demands of EVA on Gemini 8. He reassigned See to be the prime commander of Gemini 9 and put Scott as pilot of Gemini 8 and Charles Bassett as the pilot of Gemini 9.

The fourth and final rearrangement of the Gemini crew assignment occurred after the deaths of See and Bassett when their trainer jet crashed, ironically into a McDonnell building which held their Gemini 9 capsule in St. Louis. The backup crew of Stafford and Cernan was then moved up to the new prime crew of the re-designated Gemini 9A. Lovell and Aldrin were moved from being the backup crew of Gemini 10 to be the backup crew of Gemini 9. This cleared the way through the crew rotation for Lovell and Aldrin to become the prime crew of Gemini 12.

Along with the deaths of Grissom, White, and Roger Chaffee in the fire of Apollo 1, this final arrangement helped determine the makeup of the first seven Apollo crews, and who would be in position for a chance to be the first to walk on the Moon.

In his autobiography Deke! Slayton relates that he would probably have replaced Aldrin with Cernan, the backup pilot for Gemini 12, on Apollo 11 if the second use of the Astronaut Maneuvering Unit (AMU) had been on Gemini 12. (The first use was by Cernan on Gemini IX-A.) Cernan makes a similar claim in his autobiography.

As it happened, despite these random substitutions and similar ones in Apollo, and a different number of unmanned flights in both programs, Slayton's rotation philosophy dominated to create a curious coincidence: most of the Gemini astronauts who went on to fly in Apollo occupied an Apollo mission numbered one more than their corresponding Gemini mission:

- Schirra commanded Gemini 6 and Apollo 7.

- Borman and Lovell flew together on Gemini 7 and Apollo 8.

- David Scott flew on Gemini 8 and Apollo 9.

- Stafford and Cernan flew together on Gemini 9A and Apollo 10.

- Collins flew on Gemini 10 and Apollo 11.

- Conrad and Gordon flew together on Gemini 11 and Apollo 12.

- Lovell commanded Gemini 12 and Apollo 13.

The only exceptions to this pattern were:

- McDivitt, who commanded Gemini 4 and Apollo 9

- Young, who flew Gemini 3, Gemini 10, and Apollo 10

- Armstrong, who commanded Gemini 8 and Apollo 11

Missions

There were 12 Gemini flights, including two unmanned flight tests. All were launched by Titan II rockets.

| Mission | LV Serial No | Mission Dates | Launch Time | Duration | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemini 1 | GLV-1 12556 | 8–12 April 1964 | 16:01 UTC | 03d 23h | First test flight of Gemini |

| Gemini 2 | GLV-2 12557 | 19 January 1965 | 14:03 UTC | 00d 00h 18m 16s | Suborbital flight to test heat shield |

| Mission | LV Serial No | Command Pilot | Pilot | Mission Dates | Launch Time | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemini III | GLV-3 12558 | Grissom | Young | 23 March 1965 | 14:24 UTC | 00d 04h 52m 31s | |

| First manned Gemini flight, three orbits. | |||||||

| Gemini IV | GLV-4 12559 | McDivitt | White | 3–7 June 1965 | 15:15 UTC | 04d 01h 56m 12s | |

| Included first extravehicular activity (EVA) by an American; White's "space walk" was a 22 minute EVA exercise. | |||||||

| Gemini V | GLV-5 12560 | Cooper | Conrad | 21–29 August 1965 | 13:59 UTC | 07d 22h 55m 14s | |

| First week-long flight; first use of fuel cells for electrical power; evaluated guidance and navigation system for future rendezvous missions. Completed 120 orbits. | |||||||

| Gemini VII | GLV-7 12562 | Borman | Lovell | 4–18 December 1965 | 19:30 UTC | 13d 18h 35m 01s | |

| When the original Gemini VI mission was scrubbed because its Agena target for rendezvous and docking failed, Gemini VII was used for the rendezvous instead. Primary objective was to determine whether humans could live in space for 14 days. | |||||||

| Gemini VI-A | GLV-6 12561 | Schirra | Stafford | 15–16 December 1965 | 13:37 UTC | 01d 01h 51m 24s | |

| First space rendezvous accomplished with Gemini VII, station-keeping for over five hours at distances from 0.3 to 90 m (1 to 300 ft). | |||||||

| Gemini VIII | GLV-8 12563 | Armstrong | Scott | 16–17 March 1966 | 16:41 UTC | 00d 10h 41m 26s | |

| Accomplished first docking with another space vehicle, an unmanned Agena stage. While docked, a Gemini spacecraft thruster malfunction caused near-fatal tumbling of the craft, which, after undocking, Armstrong was able to overcome; the crew effected the first emergency landing of a manned U.S. space mission. | |||||||

| Gemini IX-A | GLV-9 12564 | Stafford | Cernan | 3–6 June 1966 | 13:39 UTC | 03d 00h 21m 50s | |

| Rescheduled from May to rendezvous and dock with augmented target docking adapter (ATDA) after original Agena target vehicle failed to orbit. ATDA shroud did not completely separate, making docking impossible. Three different types of rendezvous, two hours of EVA, and 44 orbits were completed. | |||||||

| Gemini X | GLV-10 12565 | Young | Collins | 18–21 July 1966 | 22:20 UTC | 02d 22h 46m 39s | |

| First use of Agena target vehicle's propulsion systems. Spacecraft also rendezvoused with Gemini VIII target vehicle. Collins had 49 minutes of EVA standing in the hatch and 39 minutes of EVA to retrieve experiment from Agena stage. 43 orbits completed. | |||||||

| Gemini XI | GLV-11 12566 | Conrad | Gordon | 12–15 September 1966 | 14:42 UTC | 02d 23h 17m 08s | |

| Gemini record altitude, 1,189.3 kilometres (739.0 mi) (739.2 mi) reached using Agena propulsion system after first orbit rendezvous and docking. Gordon made 33-minute EVA and two-hour standup EVA. 44 orbits. | |||||||

| Gemini XII | GLV-12 12567 | Lovell | Aldrin | 11–15 November 1966 | 20:46 UTC | 03d 22h 34m 31s | |

| Final Gemini flight. Rendezvoused and docked manually with its target Agena and kept station with it during EVA. Aldrin set an EVA record of 5 hours 30 minutes for one space walk and two stand-up exercises, and demonstrated improvements to previous EVA problems. | |||||||

Gemini-Titan launches and serial numbers

The Gemini-Titan launch vehicles, like the Mercury-Atlas vehicles before them, were ordered by NASA through the U. S. Air Force and were in reality missiles. The Gemini-Titan II rockets were assigned U.S. Air Force serial numbers, which were painted in four places on each Titan II (on opposite sides on each of the first and second stages). U.S. Air Force crews maintained Launch Complex 19 and prepared and launched all of the Gemini-Titan II launch vehicles.

The USAF serial numbers assigned to the Gemini-Titan launch vehicles are given in the tables above. Fifteen Titan IIs were ordered in 1962 so the serial is "62-12XXX", but only "12XXX" is painted on the Titan II. The order for the last three of the fifteen launch vehicles was cancelled on 30 July 1964, and they were never built. Serial numbers were, however, assigned to them prospectively: 12568 - GLV-13; 12569 - GLV-14; and 12570 - GLV-15.

Current location of hardware

Spacecraft

Gemini 1

- Destroyed

Gemini 2

- Air Force Space & Missile Museum, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla.

Gemini III

- Grissom Memorial, Spring Mill State Park, Mitchell, Ind.

Gemini IV

- National Air and Space Museum, Washington D.C.

Gemini V

- Johnson Space Center, NASA, Houston, Texas

Gemini VI

- Oklahoma History Center, Oklahoma City, Okla.

Gemini VII

- Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, Chantilly, Va.

Gemini VIII

- Armstrong Air and Space Museum, Wapakoneta, Ohio

Gemini IX

- Kennedy Space Center, NASA, Cape Canaveral, Fla.

Gemini X

- Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center, Hutchinson, Kan.

Gemini XI

- California Museum of Science and Industry, Los Angeles, Calif.

Gemini XII

- Adler Planetarium, Chicago, Ill.

Trainers

Gemini 3A - St. Louis Science Center, St. Louis, Mo.

Gemini MOL-B - National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio

Gemini Trainer - U.S. Space & Rocket Center, Huntsville, Ala.

Gemini Trainer - Goddard Space Flight Center (Visitor Center), NASA, Greenbelt, Md.

Gemini Trainer - Louisville Science Center, Louisville, Ken.

6165 - National Air and Space Museum, Washington D.C. (not on display)

El Kabong - Kalamazoo Air Museum, Kalamazoo, Mich.

Gemini Trainer - Kalamazoo Air Museum, Kalamazoo, Mich.

TTV-2 Royal Museum, Edinburgh, Scotland

Trainer - Pate Museum of Transportation, Fort Worth, Texas

MSC 313 - Private residence, San Jose, Calif.

Rogallo Test Vehicle - White Sands Space Harbor, White Sands, N. M.

TTV-1 - Stephen F. Udvar-Hazy Center, Chantilly, Va.

unnamed - U.S. Air Force Space Museum, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla.

unnamed - U.S. Air Force Space Museum, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla.

Gemini Trainer - BDL Aerospace and Flight Museum, NAS Whidbey Island, Oak Harbor, WA.

Trainer - U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame, Titusville, Fla.

MSC-307 - USS Hornet Museum, Alameda, Calif.

Proposed applications

McDonnell Aircraft was one of the original bidders on the prime contract for Apollo, but lost out to North American Aviation. McDonnell later sought to extend the Gemini program by proposing a derivative which could be used to fly a cislunar mission and even achieve a manned lunar landing earlier and at less cost than Apollo, but these proposals were rejected by NASA.

Military

The United States Air Force had an interest in the system, and decided to use its own modification of the spacecraft as the crew vehicle for the Manned Orbital Laboratory. To this end, one of the unmanned Gemini spacecraft was refurbished and flown again atop a mockup of the MOL, sent into space by a Titan III-M. This was the first time a spacecraft went into space twice.

The USAF also had the notion of adapting the Gemini spacecraft for military applications, such as crude observation of the ground (no specialized reconnaissance camera could be carried) and practicing making rendezvous with suspicious satellites. This project was called Blue Gemini. The US Air Force did not like the fact that Gemini would have to be recovered by the US Navy, so they intended for Blue Gemini eventually to use the paraglider and land on three skids, something from the original design of Gemini.

At first some within NASA welcomed sharing of the cost with the USAF, but it was later agreed that NASA was better off operating Project Gemini by itself. MOL was cancelled in 1968 and Blue Gemini too was cancelled without any use by military astronauts.

Other proposals

Other Gemini derivatives were proposed, including Big Gemini, Gemini LOR, Gemini Lunar Lander, Gemini-Centaur, Gemini Ferry, Gemini Transport, Gemini - Saturn I, Gemini - Saturn IB, Gemini - Saturn V, Gemini Pecan, Extended Mission Gemini, Gemini - Double Transtage, Gemini Satellite Inspector, Gemini Lunar Surface Rescue Spacecraft, Gemini Observatory, Gemini Para glider, Rescue Gemini, Winged Gemini, Gemini LORV and Gemini Lunar Surface Survival Shelter.[4]

See also

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration

- Titan (rocket family), including the Titan II rocket

- Big Gemini

- Blue Gemini

- Manned Orbital Laboratory

- Splashdown

- Agena Target Vehicle

- Timeline of hydrogen technologies

- Space exploration

- U.S. space exploration history on U.S. stamps

- Space suit

- Spacecraft

References

- ↑ The only Gemini spacecraft not on a Titan II was the re-flight of Gemini 2 for a Manned Orbital Laboratory test in 1966, which used a Titan IIIC

- ↑ Gemini Program. Venice, CA: Revell, Inc.. 1965. pp. 1. pamphlet included with 1/24 scale model of Gemini spacecraft; based on official records of NASA.

- ↑ Farmer, Gene; Dora Jane Hamblin (1970). First On the Moon: A Voyage With Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr.. Boston: Little, Brown and Co.. pp. 51–54. Library of Congress 76-103950.

- ↑ Astronautix Gemini

Further reading

- Francis French and Colin Burgess, In the Shadow of the Moon: A Challenging Journey to Tranquility, 1965-1969. History of the entire Gemini program.

- Gene Kranz, Failure is Not an Option. Factual, from the standpoint of a chief flight controller during the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo space programs. ISBN 0-7432-0079-9

- David M. Harland, How NASA Learned to Fly in Space: An Exciting Account of the Gemini Missions, Apogee Books, 2004, ISBN 1-894959-07-8

- David J. Shayler, Gemini, Springer-Verlag Telos, 2001, ISBN 1-85233-405-3

- On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini - (NASA report SP-4203) (PDF format)

- Project Gemini - A Chronology (NASA report SP-4002) (PDF format)

- Gemini Midprogram Conference - Including Experiment Results (NASA report SP-121) - Manned Spacecraft Center - Houston, Texas, February 23-25, 1966

- Gemini Summary Conference (NASA report SP-138) - Manned Spacecraft Center - Houston, Texas, February 1–2, 1967

External links

- On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini by Barton C. Hacker and James M. Grimwood

- John F. Kennedy Space Center - The Gemini Program

- NASA Project Gemini site

- Space history: Gemini Program space history - Gemini missions spaceflight

- Project Gemini Drawings and Technical Diagrams

- Technical Diagrams and Drawings

- Gemini familiarization Manuals (PDF format).

- Gemini Designer Jim Chamberlin Bio

- Direct Flight Apollo Study: Gemini Spacecraft Applications : document on the proposed Gemini-based Apollo program.

- NASA History Series Publications (many of which are on-line)

Archival Materials

Related content

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||